About art and wine: two worlds that meet.

There is one wish that people often make at the end of a guided tour. After having spent the day clocking up the miles and being overwhelmed by immortal art, they always say: where can we drink a good Spritz now?

After all, Italy is the land of aperitivo, which usually consists of a glass of wine and various snacks. At the end of an exhausting and emotional tour, you want to sit down somewhere, relax and have a drink in company. Sitting in front of a glass of Prosecco or Cesanese (depending on your preference), you let the impressions of the last hours sink in, talk about what you have seen and exchange ideas. Somehow the experience continues, because drinking wine is also a sensory experience and it emphasises the taste of things (there is even a type called contemplative wine).

In Italy, there are around 144 native, often ancient grape varieties from which countless good and excellent wines are made, either purely varietal or by blending several types of grapes (Bordeaux style). In other words, one is spoilt for choice.

In our day and age, a good wine is first of all a symbol of pleasure, joie de vivre and sharing. What makes it so seductive is the thrill that wine imparts, which leads to more freedom and confidence in behaviour. A fascination whose roots reach far into the past. As early as the Greek and Roman age, wine was consumed at Bacchanalia, with the result that the consequent euphoria led men and women to uncontrolled sexual conduct and cruel ritual murders for several days. Throughout the celebration, laws and moral codes were suspended to such an extent that, at some point, the event had to be banned in Rome. Those rites celebrated Dionysus, the god of lifeblood, the primordial element of the cosmos, the frenetic current of life that pervades everything. Such practices had propitiatory features and were performed on the occasion of sowing and harvesting. Dionysus embodies the primordial, instinctive spark that is present in every living being. As far back as the Greek world, Dionysian rituals were quite wild. Originally only women, called Bacchae, were involved and supposedly they roamed the forests tearing fawns apart and devouring them on the spot while dancing and singing unbridled.

There is a marvellous painting by Caravaggio that depicts the god of wine as no one else has done. While in Rome at the end of the 16th century, Caravaggio was commissioned by Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte to paint Bacchus for Grand Duke Ferdinand I de Medici. The painting was exhibited for centuries in the historic Villa d'Artimino in the Carmignano wine-growing area of Tuscany. And there it is, in a nutshell, the essence of Epicurean pleasure: a young and seductive wine god looks straight into our eyes, offering a glass of Chianti and inviting us to join his table. Details that leave us breathless are the still-life in the foreground and the crown of vine leaves on the god's head, painted with the realism of Caravaggios’ famous light. To the side, a glass jug with the rest of the wine and, hidden in the light’s reflection, a self-portrait of the artist himself.No other painting in Italian art history can illustrate the ancient and profound connection between art and wine better than this one. Caravaggio's style is modern because it involves the viewer by addressing his senses. As a result, his paintings are primarily a physical and emotional experience, which only later becomes intellectual. The first sense to be engaged is sight, through the brightness of oil colours, which has remained intact over the centuries. Our emotions resonate as we enjoy the interplay of hues recalling autumnal soils and leaves with the last breath of summer, just as when we observe the nuances of a Sangiovese against the surface of a glass, trying to catch with our sense of smell its spicy and undergrowth scents as well as those of ripe fruit, once the bouquet of aromas will have opened up. It is the same fruit we see displayed in the painting’s foreground, on the table in front of the god; we almost feel as if we can touch it, so convincingly it is represented.

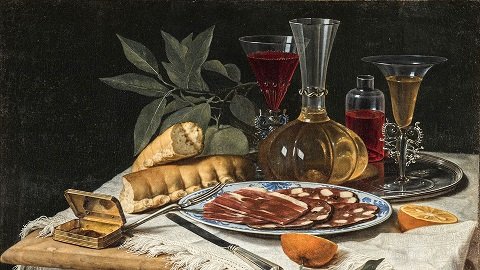

In the 17th century in Rome, the theme of still-life takes on a philosophical significance, precisely through the work of Caravaggio and Northern European artists active in the capital at that time. Such representations developed into metaphors dealing with the transience of life. A visual representation of the biblical vanitas vanitatum et omnia vanitas (vanity of vanities, and all is vanity) and the Catholic memento mori (remember that you will die). This brings to mind an episode that occurred a few decades earlier: during his pontificate, Paul III Farnese confirmed Michelangelo Buonarroti's commission for the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel and, more or less at the same time, entrusted his cellar master Sante Lancerio with the creation of what was probably Italy's first wine guide, entitled Della natura dei vini e dei Viaggi di Paolo III ("On the Nature of Wines and the Travels of Paul III"). In other words, Roman Catholicism of that era is imbued with a Weltanschauung reflecting on end times and also enjoying the pleasures of the present. Magnificient later examples of this art movement are still-lifes by the German painter Christian Berentz, which can be admired in the Galleria Corsini in Trastevere. Looking at Lo spuntino elegante (The Elegant Snack), we learn the concept of aperitivo, as we understand it today, is nothing new. Arranged on an elegant porcelain plate are hand-cut salami and ham, accompanied by fresh bread ready to be broken by hand. Next to it, on a silver tray, we see two precious crystal goblets filled with white and red wine, perhaps Frascati and Lambrusco, together with their respective jugs. The contrast between refined cutlery, Murano glass, gilded snuff box and simple food emphasises the realism and virtuosity of the painter. The climax is reached in the halved, somewhat withered orange as well as in the corner of the wooden table exposed by the displaced tablecloth.

What is reflected here is one of the many ordinary moments of everyday life, which was captured to give the illusion that time can be stopped. The scene is deliberately not frontal, to show the uncertainty of existence and its constant fluctuation between more or less significant moments. Even in the painting Natura Morta con Savoiardi (Still-life with Ladyfingers), also known as La Mosca (The Fly), the attempt to stop time is entrusted to an insect. The fly has landed on one of the biscuits, reminding us that pleasure is ephemeral and that we might as well enjoy it.

When I am in front of these magnificent paintings, I pause to reflect on that the wine in the goblets had to be sweet. It was not until the 19th century in the province of Bordeaux (France), that the fermentation technique was perfected to create the famous, strictly dry red wines that served as inspiration throughout the world and helped to shape what has become contemporary taste today. Barolo, Chianti or Amarone would not exist as we know them today if Juliette Colbert, a French aristocrat who married the Marquis Falletti di Barolo in 1806, had not brought her trusted oenologist to Piedmont because she was horrified by Italian wines, which she found too sweet. So for a long time, in Europe, people drank a very different wine from the one we know today.

Over the centuries, wine has retained its refined character as well as, albeit transfigured, the liberating power of inebriation, considered sacred in antiquity and to a certain extent in the Christian world (Eucharist). For wine is by all means the nectar of the gods, since it is, itself, a work of art. As the result of hard, human labour and a complex production process, wine represents the reward of all toil and suffering. Wine unites nobles and peasants in their pursuit of happiness, which is always temporary and elusive. It lifts the spirit and loosens the tongue, inducing one to abandon inhibitions to the last, that is, to the truth. In vino veritas is the old saying, or to quote Horace, "Inebriation reveals hidden things". It is a quest then, in nothing dissimilar to the path taken by the artist in his aspiration to beauty understood in its deepest meaning, that is, of harmony governing the relationship between man and the world. The colours of a painting are commonly described in terms of brilliance, vivacity, fullness and transparency (think of Leonardo da Vinci's glazes), i.e. the same vocabulary referred to when describing the tones of wine during a tasting. Both in a painting and a glass of wine we find an enormous evocative power, generated by the impressions that resonate in our memory. Incidentally, the vine, with its climbing branches and elegantly jagged leaves, possesses an aesthetic value of its own and, apart from its symbolism, it is incredibly common in the motifs of ancient Roman mosaics, sarcophagi and in the frescoes of catacombs.

Even further, Italian wine and art share something that is perhaps even more intimate than the pursuit of beauty: landscape. Italian frescoes are rich in views with well-tended vineyards, which in the Middle Ages were meant to symbolise the good governance of Communes. It is no coincidence that major wine producers are often also important art collectors. This also means that the territories from which famous artists come are the same ones where great wines have been produced for centuries. Art and wine thus share a geographical, almost physical identity that has developed through a centuries-long cultural process into a completely consistent point of view. But what is that point of view?

At first glance, it appears to be Horace’s carpe diem, also expressed by Lorenzo the Magnificent at the end of the 15th century in his Carnival song The Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne:

Fair is youth and void of sorrow

But it hourly flies away

Youths and maids enjoy to-day!

Nought ye know about tomorrow.[1]

In other words, an exhortation to enjoy the moment because nothing in life is certain, predictable or lasting. We enjoy beauty, love and senses while they exist, for they are fleeting and no one knows what will happen tomorrow.

In my opinion, however, there is more behind it; an expansion of the field of vision rather than a specific attitude. A keyhole through which we look and feel intense impressions connected to both the present and memories. As we continue our sensory journey, whether through a painting or a glass of wine, our feelings and thoughts take us back further and further into past, interconnected worlds. Our reminiscences, awakened by sensory perceptions, merge with echoes of ancient beliefs and ways of life. The result is a profound increase in pleasure that is no longer fleeting and temporary but rather becomes richer, more varied and lasting. Therefore, it is the knowledge that succeeds in stopping time, at least in our imagination. All this had already been sensed in antiquity. Epicurus says: " "I for my part cannot imagine what good is if I disregard the pleasures of taste, the pleasures of love, the pleasures of hearing, those arising from the beautiful images perceived by the eyes, and in general all the pleasures that men have from senses. It is not true that only the joy of mind is good; for the mind rejoices in the hope of sensible pleasures, in the enjoyment of which human nature can free itself from pain."

I will conclude with Arcimboldo's bizarre and original depiction of Autumn, a work that illustrates better than a thousand words the intimate relationship between man, wine and agriculture. Portrayed in profile we see a human-like figure composed of seasonal vegetables and fruits such as potatoes, cabbage, mushrooms, grapes and whatnot. The bust consists of a barrel, indicating the time of grape harvest and winemaking. Such a curious image reminds us of an agricultural deity, underlining the ancient connection between man and the seasons as well as the rituals associated with them like the grape harvest, which has remained important over the centuries, probably because human needs have remained unchanged over time. The vine has always been a metaphor for human existence; for its long roots that recall belonging, but also and especially for the idea of hard work followed by a well-deserved reward.

[1] Alison Chapman (ed.) and the DVPP team, “The Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne. Lorenzo De’ Medici’s Carnival Song,” Digital Victorian Periodical Poetry Project, Edition 0.98.5beta, University of Victoria, 14th October 2022, https://dvpp.uvic.ca/cornhill_series/1877/pom_12302_the_triumph_of_bacchus_and.html.

Mediagraphy:

Commonists (2021), Bacchus by Caravaggio, public domain, January 17, 2023.

Web Gallery of Art, Elegant snack by Christian Berentz, public domain, November 12, 2022.

Web Gallery of Art, Still life with Crystal Glasses and Sponge Cakes by Christian Berentz, public domain, January 17, 2023.

http://members.tripod.com/dianapitocco/I%20Mesi.htm, October by Maestro Venceslao, public domain, November 15, 2022.

Arcomboldo, Giuseppe (1573), Autumn, public domain, January 17, 2023.